[1] Dr John Swallow was Principal Scientist on the cruise and a legend amongst oceanographers. Known as “Big John” he was large and strong, but quiet spoken. Big John seemingly never slept during a cruise and could seem to be omni-present. If you made a mistake in annotating a logbook you would later find a neat correction inserted by Big John. But he had a gentle wit. The story went that in correcting one young scientist he was heard to say “Don’t worry lad, everyone makes mistakes, even I thought I had once, but then it turned out I was wrong”.

[1] Dr John Swallow was Principal Scientist on the cruise and a legend amongst oceanographers. Known as “Big John” he was large and strong, but quiet spoken. Big John seemingly never slept during a cruise and could seem to be omni-present. If you made a mistake in annotating a logbook you would later find a neat correction inserted by Big John. But he had a gentle wit. The story went that in correcting one young scientist he was heard to say “Don’t worry lad, everyone makes mistakes, even I thought I had once, but then it turned out I was wrong”.

The photo shows Big John taking a bottle from the wire during a different cruise (possibly in the Indian Ocean). When taking a water bottle of the wire you could tell if it was Big John who had put it on because the clamp would be almost impossible to undo. However, there was no way he could have squeezed his large frame through the small gap by which we could open the locker against the stationery strewn across the floor inside. In this case my smaller stature was actually useful.

[2] In those days not only did the stewards make ones bunk, they also brought scientists an early morning cup of tea. At the start of a cruise this was a mixed blessing. I was sharing the S9 cabin and had the upper bunk. If you were feeling queasy and was handed a cup of tea you were trapped in your bunk until you drank it!

[3] Breakages meant that drinking cups were often in short supply and experience taught one to take your own mug with you on cruises… and look after it whilst at sea!

[4] Precision Depth Recorder. A deep ocean echo sounder that recorded the echo signal on a “

Mufax” recorder which “burnt” a trace of chemically coated paper producing much ozone in the process. It was necessary to sit by the machine and keep count of how many times the width of the paper had been traversed to date so that the actual depth could be written on the recording at regular intervals.

If you lost count of the number of traverses then one could listen over headphones to the outgoing ping and the incoming echo and determine it that way. The same headphones could be used to listen to dolphins and pilot whales when they were close to the ship.

Somewhat eerily one sometimes heard human voices apparently coming from the deep. These were due to RF interference caused by someone making a ship to shore telephone call and we would politely take off the headphones until the conversation had ceased!

Somewhat eerily one sometimes heard human voices apparently coming from the deep. These were due to RF interference caused by someone making a ship to shore telephone call and we would politely take off the headphones until the conversation had ceased!

The research ships were amongst the few non-military vessels with echo sounders capable of determining the depth (typically 2 to 6km) of the open ocean and often they worked away from the shipping lines. Thus the echo sounder was routinely used on passage legs of oceanographic cruises. To achieve the required depth range the sounder was transmitted and received by a “fish” towed to one side of the ship. This reduced sound pickup from the ship itself and minimised the effect of bubbles caused by the ship’s passage through the water.

We leave Barry; the stationery cupboard gets trashed; rough weather; I find my sea legs; a fire on the Bridge…

We leave Barry; the stationery cupboard gets trashed; rough weather; I find my sea legs; a fire on the Bridge…

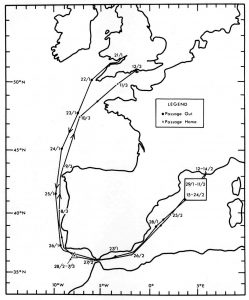

Wednesday (21 Jan 1970): 1430: Joined ship. left Barry about 2000hrs through the lock gates.

2130hrs: Ships compass adjusted. Sea fairly calm, wind light increasing during the night.

Thursday (22 Jan): Sunny morning spent on deck watching the sea. Helped in assembly of tide gauge in afternoon.

Sea much rougher. Porpoise joined ship and played alongside within 7 feet of the side. Could be seen underwater cutting back and forth under the ship.

Sea much rougher. Porpoise joined ship and played alongside within 7 feet of the side. Could be seen underwater cutting back and forth under the ship.

Number of Gannets around. Clocks go back to GMT overnight.

Friday (23 Jan): Wind 70kt during night, sea very rough, ship rolling violently. A number of instruments shifted in the night and had to be secured. The stationery locker was a shambles, I squeezed in and cleared enough room to open the door and [the Principal Scientist] John Swallow 1: Big John and I began tidying up. The heat and pitching felt in the forward locker cancelled any thought of lunch.

A brief (2 – 3 minutes) run of the ship-borne wave recorder produced two 30 foot waves and standing at the stern looking aft the seas are spectacular. Where a lot of air is entrained the seas seem to glow, a brilliant light blue.

Too rough to lay tide gauge, ship hove to at 2 knots during morning but assumed course at 6 kt in pm and rolling greatly. Thermometer calibration curves got soaked last night and had to be copied out during afternoon. Am becoming adapted to the rolling and pitching.

We now have two blankets and got our beds made though a number of the stewards are still sick 2:Steward service. Tea break was a shambles – many cups in the galley were broken and we abandoned it when a steward scalded himself. The galley floor was awash with broken crockery 3:bring a mug.

Actually appreciated dinner.

PDR4: Precision Depth Recorder watch started at 1200 to get soundings across the Bay of Biscay.

Saturday (24 Jan): 0900hrs Wind freshening about force 8, ship heading 200°, 4 kt into seas. Pitching. Wrote up Diary to here. Took some photographs. Helped in manhandling TSD apparatus.

Saturday (24 Jan): 0900hrs Wind freshening about force 8, ship heading 200°, 4 kt into seas. Pitching. Wrote up Diary to here. Took some photographs. Helped in manhandling TSD apparatus.

Stood on deck below bridge watching the bows rise and fall. Very little to do in afternoon, learnt workings of the PDR equipment, had shower. In evening film “Sailor Beware” followed by [time in the] bar.

2330: ship’s siren gave long continuous blast signalling a fire on bridge, minor excitement. Weather is getting calmer.

[Previous: Introduction] [Next: to Gulf of Lion] [Photos – Barry to Gulf of Lyon]

We leave Barry; the stationery cupboard gets trashed; rough weather; I find my sea legs; a fire on the Bridge…

Sea much rougher. Porpoise joined ship and played alongside within 7 feet of the side. Could be seen underwater cutting back and forth under the ship.

Sea much rougher. Porpoise joined ship and played alongside within 7 feet of the side. Could be seen underwater cutting back and forth under the ship. Saturday (24 Jan): 0900hrs Wind freshening about force 8, ship heading 200°, 4 kt into seas. Pitching. Wrote up Diary to here. Took some photographs. Helped in manhandling TSD apparatus.

Saturday (24 Jan): 0900hrs Wind freshening about force 8, ship heading 200°, 4 kt into seas. Pitching. Wrote up Diary to here. Took some photographs. Helped in manhandling TSD apparatus.

[1] Dr John Swallow was Principal Scientist on the cruise and a legend amongst oceanographers. Known as “Big John” he was large and strong, but quiet spoken. Big John seemingly never slept during a cruise and could seem to be omni-present. If you made a mistake in annotating a logbook you would later find a neat correction inserted by Big John. But he had a gentle wit. The story went that in correcting one young scientist he was heard to say “Don’t worry lad, everyone makes mistakes, even I thought I had once, but then it turned out I was wrong”.

[1] Dr John Swallow was Principal Scientist on the cruise and a legend amongst oceanographers. Known as “Big John” he was large and strong, but quiet spoken. Big John seemingly never slept during a cruise and could seem to be omni-present. If you made a mistake in annotating a logbook you would later find a neat correction inserted by Big John. But he had a gentle wit. The story went that in correcting one young scientist he was heard to say “Don’t worry lad, everyone makes mistakes, even I thought I had once, but then it turned out I was wrong”. [4] Precision Depth Recorder. A deep ocean echo sounder that recorded the echo signal on a “

[4] Precision Depth Recorder. A deep ocean echo sounder that recorded the echo signal on a “ Somewhat eerily one sometimes heard human voices apparently coming from the deep. These were due to RF interference caused by someone making a ship to shore telephone call and we would politely take off the headphones until the conversation had ceased!

Somewhat eerily one sometimes heard human voices apparently coming from the deep. These were due to RF interference caused by someone making a ship to shore telephone call and we would politely take off the headphones until the conversation had ceased!